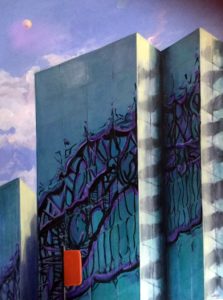

Caption: Syncopated images of the city.

Artist Louise Beck loves being in the thick of things

The bus stops outside, the park across the way is a green solace and with its swimming pool, home to a steady flow of people. Cafes of all design vintages and styles, foods and specialist coffees, dot the urban landscape, and the Factory Theatre is down the road.

When long-time artist Louise Beck decided finally that she had to open her own gallery, there was the slight obstacle of where to have it. A patient, painstaking search followed until she found her spot at 371 Enmore Road; her city gallery/studio would happen here.

Beck’s November retrospective showcases work from her Gallery 371 which will also be celebrating three years. The oils feature Skyscapes which, as she writes, “focus on Sydney and its glass skyscrapers, their reflections, their distortions and their refraction of light, colour and image. The result is an organic and somewhat surreal view of our wonderful city.”

It was this depiction of the newest and the most historic city buildings that first attracted me to her work. I had heard about Beck via Thanh Tam Cao Tam, who had been part of students’ groups at Julian Ashton Art School and still sees her.

I visited Gallery 371 as part of an Inner West creativity trail, and it took a while to click why Beck’s name was familiar to me. Tam had praised her.

The trail brochure had a picture of what I like to think of as a syncopated, twisting, Centrepoint Tower, a ground-to-sky enticement, visual music to an eye accustomed to more touristy images, a commercial impulse taking you to the top.

Remarkably, two years later I find out that her best friend during student days and still a good mate is married to a cousin of mine, an Australian living in Europe. Such a connection and coincidence seemed perfectly natural in this milieu.

For someone raised in regional NSW, ending up on a busy street where cars and buses pass constantly and planes fly overhead, is not something she would have expected. Yet, Beck’s place is like a pop-in community centre. I sat on the chair behind the desk she usually sits in while she settled to the side on a stool, and we talked. At the end, she said, “I have never talked so much about myself as I have with you.” Which is all fine with me.

What was her upbringing like?

I was born in the city but grew up in the country. My father was a postmaster, so we moved around a lot. The longest place we lived was Finley, down by the Murray River NSW. We were there for six years and then came back to Sydney for high school. I got two scholarships in the late 60s) then did English and history teaching. Once I had taught off my bond the very first thing I did was resign from teaching and go to art school. I had always wanted to go. I got my training at Julian Ashton Art School.

Why did you choose the gallery’s location? What were you looking for and how does the space reflect the city’s influence on you?

I lived in Balmain for 16 years. It was an 1884 house and I had a studio upstairs. I used to struggle down the narrow, steep staircase – it had huge banisters – and I thought I was going to end up breaking my neck. I also painted in Addison Road for about six years. All the time I was thinking that I wanted to find my own art space. Then I got to know this area really well, and realised it was full of artists and was quite edgy, which Balmain wasn’t.

I like diversity. That’s why I got so bored in Balmain because there is no diversity. I miss some of my friends, but I tell you, I’ve probably met two times the number of people here than I did in Balmain.

Anyway, I kept looking for about four years, and I found this place. It had been a backpackers place and was in terrible condition but it was on the market and I thought well it’s opposite this beautiful park, has a bus stopping at that door, it’s in a nice, edgy part of the world and 10 minutes from King Street Newtown, so I thought this is it.

I had a building inspection, but they failed to find the rising damp, and then they failed to notice that upstairs was built over a box gutter, so once I had all the lighting in the gallery the ceiling then collapsed. I virtually had to rebuild this whole place. The rest of the house, mind you, was quite solid, old but solid. I had a great builder and together it took us about six months. I lived here all the time, because I was painting, getting ready for the opening exhibition.

Has the space worked out as you hoped?

To be honest when I moved here, I saw it more as a lifestyle change than as a working venture. Then I began to display my art and people came in off the street. They so obviously craved spaces like this. I opened in November (2016) and by January I had the first show of another person. It has become a business, which is lovely. I have met so many artists in this area. I was really chuffed as that was not what I set out to do. At one of the openings, I ran into a young woman who said, ‘I don’t know whether you realise this, but you have created a real artistic hub. I’ve come to a lot of your shows.”

What is particularly surprising to her?

I feel as if I am part of a community and have an open-door policy. Yet I tend to be a rather private person, so I felt at first, ‘Oh my God, I am on display here, but when the postman knows your name and you know his name, and the butcher round the corner always waves when he’s going home, that’s a lovely sense of community. I have been very fortunate.

What are you looking for in the artists that you show? Is the subject matter important?

I am not specifically looking for a particular subject but more at the artist. I quite like the idea, at this stage of my life, that I can be something of a mentor to the artists because a lot of them are younger. I have nurtured some classically trained artists. I also like the vibrancy of street art and I have had a number of street artists in here. I just love their attitude, that energy. It’s refreshing. I want a variety of artists. I have knocked back a couple who were not quite ready, but I don’t mind all those things that push boundaries. That’s what art is all about. I welcome them all, trying to break down that ridiculous mystique that we Australians seem to have developed about art and artists. I can see as people walk by they’re interested but they are too scared to come in because they think you are going to pounce. But I often find they come in more when I am here. It’s less intimidating for them. Europeans, the backpackers, just come in, and look at art and talk to you. They are not at all intimidated by it, but we Aussies, I don’t know.

The number of galleries is growing, in Glebe, for example, and I try to patronise them. The government doesn’t put a buck in the arts, you know (whereas) my son is in the film industry and they have work in New Zealand all the time.

Who is her main clientele, and do they reflect the area? I

European travellers and backpackers may not buy but they love looking. Not everyone can buy and it’s nice if they just come in and see things. I could not tell you who my average clientele is. I have neighbours who buy quite regularly, which is lovely. People come in off the street because they have seen something that they really want, but I can’t say there is a clientele as such. This is an arty area in so far as there are lot of young poor artists around. We also have the diversity of old Greeks and a lot of Aboriginals. Obviously when someone has a show, they bring their own people, and there is the gallery mailing list. There’s a bit of cross pollination going on.

The cafes round here are very supportive too. They’re great. They are always happy to take invitations for the next show.

Do you specialise in any type of paint?

Yes, oil based. I do the odd charcoal too, but have never used acrylics. I have never been interested in water colours. I like good quality oils. When you are younger you can’t necessarily afford them and I sometimes think if you really want to do something you can create it with whatever is at hand. I painted for many years with a Czech guy. We went together to the Czech Republic and painted there. We used pencil and charcoal and people treated us like royalty.

Where does the city work fit into your schedule and thought process?

I have an instinctive love of portraiture. I can whip up a portrait like that. I must do more of the portraiture, which I enjoy, but the city work intellectually stimulates me. It’s hard to say how long it takes. I tweak and do that is and that. I realise I have only touched the surface. I have been doing them for 10 years and now I know there is so much more I can do. I need more patience. Sydney can’t stand still. It is changing. This is reinforced when you paint reflections in glass. Move one inch and the reflection changes. I want to get this fluid organic quality. I want people to get that feeling of, ‘oh, what am I looking at now? Am I looking through a window or am I looking at a reflection in a window?’ I like that. I like the viewer to stop and think about it. While I did not consciously set out with that concept of chronicling, I was soon into it. I realised that was what I was doing.

Is that how art often works, taking you to places?

Absolutely. I don’t set out with a clear plan because that often hampers you, so you let the canvas speak to you a lot of the time. Nowadays, you can paint on stretch canvas and you don’t have to worry about frames, and that makes it much easier. I have always stretched my own, but for these very big canvases, it is very physical, so I now get this young guy up the road to do it for me. You have to stretch the canvas this way and then that way. I can do the small ones but the big ones, oh no. He has just started out and we celebrate our birthdays together. He carries my business cards and I carry his work. I like the community help; it is very nice.

What does the city mean to you as an artist?

It’s my life blood. I don’t understand people who want to go to the country. Three days is maximum for me. I like to be in the middle of things. I hate being able to see the horizon. It makes me feel really depressed. I always think Russell Drysdale must have been a depressed man. He has come from luscious green England and I see his paintings, and I just want to howl.

I am doing more on Newtown because it has changed but still has gorgeous facades. Paintings can show the past, present and future. I do cranes. Centrepoint Tower has a view, a skyscape (of now) but whack a crane in the background and it shows a future. I do that often in my search for new reflections,