It is always exciting to rediscover someone you remember from a different era in your life. Even better to find out that they still reflect that early experience of knowing them or, more accurately, knowing of them.

Peter Hyatt was editor of BHP’s corporate and project magazine, Steel Profile, when I was editor of BPN Building Products News as it was known in the early 1990s. (DS: As Infolink/BPN it is now part of the Indesign stable.)

Part of my initial brief was to revamp BPN. To do so, I had to know what the competition looked like. I scoured all the building product, architecture and design magazines, newsletters, advertising brochures and other print-only marketing material of the early 1990s. Digital, what was that? The competition was in gloss and matte.

Steel Profile impressed me. While it featured BHP steel and Lysaght products, they were embedded within interiors and exteriors, beautifully photographed and described, a project magazine as much as a product magazine that, when I asked around, I realised was well-regarded in those coveted architecture circles.

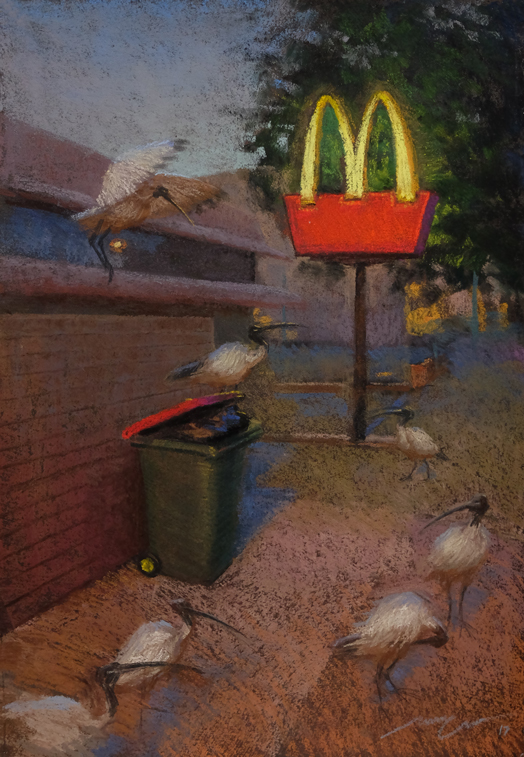

Years pass, memories fade, but it is amazing how a familiar name can flip back the decades. I had forgotten the publication until I went to Sydney’s first The Other Art Fair (OAP) 2016 and saw a series of syncopated vivid squares filling a shiny canvas, an image pulsating with energy and colour.

I looked for a name on the gallery booth. Peter Hyatt, of course. The fair was packed and generated a sort-of productive bedlam. Somehow, we managed to hear each other’s banter. I introduced myself. Peter remembered BPN though probably not my name. Nevertheless, buoyed by the ebullient atmosphere I mentioned my nascent idea for city makers. We have kept in touch ever since.

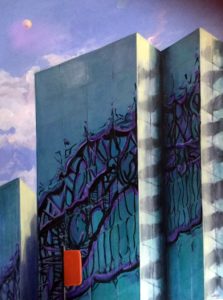

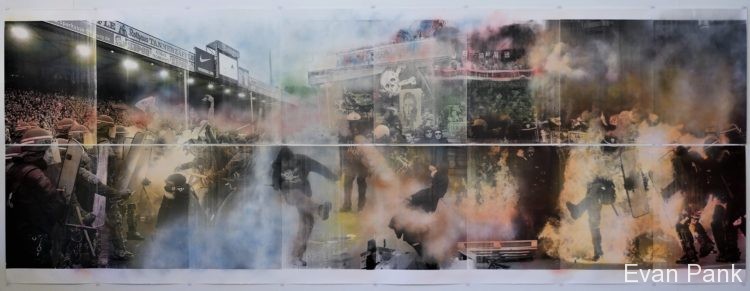

My hopes for a city-related contribution from Peter came good. About a year later I received an email with the subject line, Tattooed City. I opened the accompanying URL imagining there would be hipsters’ limbs festooned with inky sprawls. Wrong – far too prosaic. Peter’s images were athletic, poetry in motion astride a canvas of building facades, an arresting juxtaposition of digital artistry. Where was this coming from?

Here follows Peter’s answers to my city-making questions, which encompass his professional history, publishing prowess and views of where architecture fits into city building.

What is Tattooed City about?

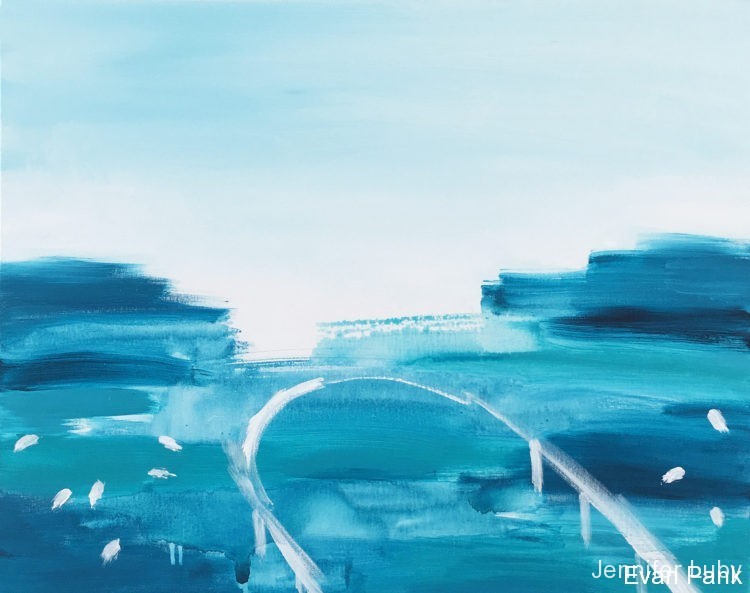

It’s an exploration of the darker yet sometimes more lyrical qualities of design. Cities are composed of a complex DNA. The human form absorbed onto and into buildings makes a connection as to why buildings are made and what they offer, not merely as containers but occasionally with functionality and artistry. Think of Frank-Lloyd Wright’s coiled New York Guggenheim, Norman Foster’s game-changing Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank and Jean Nouvel’s latest art gallery in Abu Dhabi.

Do you believe it marks a shift for you from commercial to fine-art photography?

In many ways it’s a natural evolutionary process. Personal work is a pretty important expression of who you are. Much more so than commercial photography where you record the work of others. Private work is your own invention and your own freedom.

I like to say that the film side of my work gives a project wings – in other words it allows projects to travel around the globe rather than remain earthbound in the one spot. Private work is similar. It frees me to explore other possibilities and to be my own client.

It’s less of a shift than a development from 30-plus years shooting and filming commercial work. A fine-art approach has always been there but now there is a greater abstraction to the images and this is most evident in the recent series, Incandescent and Tattooed City. These are products of my own invention rather than shot to a brief. It’s liberating and testing to be as original and inventive as possible. Interestingly both themes really consider the urban condition of crowded cities with the largely solitary figure.

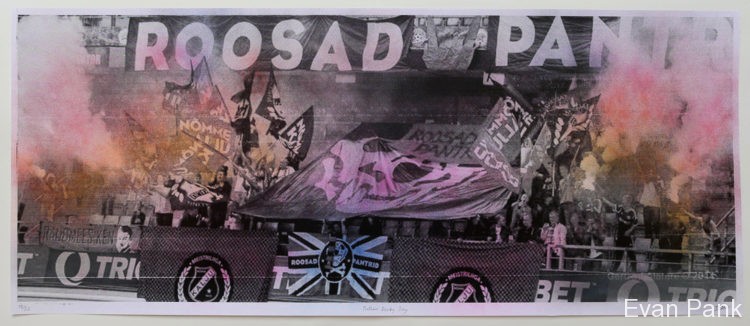

Incandescent explores the city as dark carnival. High-voltage images comprising points of light and shadow are transformative windows-to-the-world. Vivid, abstract mosaics are achieved through veil, focus and structure to give subjects greater energy and voice. Tattooed City continues this exploration of the city as a canvas to re-imagine buildings and their creators.

The figures of dancers and gymnasts are an interesting metaphor. Why did you choose this approach?

Tattooed City explores the role of the architect in city-making. The architect is depicted throughout in a shadow-play of graceful dancer or darker force projected onto their creations. In effect, the architects are tattooed into the fabric of their work, striking poses, athletic and balletic, celebrating or escaping their creations. They are consummate performers with a haunting presence and connection to their work. While their buildings are solid, the architects are enigmatic as shadow, spectre and silhouette. Tattooed City reveals the dance of design, variously sublime and deeply flawed. Architecture is easily steered off course by pragmatism so I’m trying to reveal the often-precarious nature of the designer’s role as athletic and yet vulnerable.

Where did you find the dancers and gymnasts and was it difficult to persuade them to be involved?

The dancers and gymnasts were photographed anonymously, and they remain that way – purely as silhouettes, shadow and outline. They aren’t meant to be recognisable but rather symbolic, emblematic, abstract. I wanted to tighten the association between the designer and various buildings, not so much literally as figuratively, and I liked the idea that black and white better conveys the idea of the tattoo. Once buildings are handed over, it is as if the architect is handing over their child. Hopefully, it’s a well-behaved, fully considerate child who will delight, as well as protect, their occupants. The architect as fleeting shadow represents the transitory nature of their own involvement. Tattooed City is an attempt to acknowledge this imprint or DNA in designs mostly, but not always, as a positive.

What, and where, are the buildings and why did you choose them?

The buildings and structures are diverse and mostly drawn from Melbourne and Sydney. A number are highly identifiable such as the Sydney Opera House, Bolte Bridge and Manchester Unity from Melbourne. Utzon was, of course, a genius and yet even he grappled with the complexities of bureaucracy and budget constraints. In one image, the architect resembles a cliff climber clinging precariously to the underside of a rock ledge yet athletic enough to prevail. Each image has a similar story of the human form coiled, compressed or extended to achieve the required task.

How did you set up the tattooed artists and their poses?

The wonders of Photoshop came to my aid here and involved countless hours of blending images and inventing to seamlessly create details for a fit between the architect as gymnast/dancer with the buildings I photographed. I see a strong correlation between the artistry of these other disciplines in the line and form of all the best buildings. Great buildings have great bones, musculature and skin. Their beauty is fantastic to behold. I wanted to convey that sense of wonder in these images that I hope celebrate some of the best that as humans we can realise.

Why select this particular imagery and how long did it take to create each scene?

Longer than I imagined. I found myself engrossed in producing each image. The parallel with architecture and dance is that with hard work the final product appears relatively effortless even though we might marvel at how such a thing was achieved. I think the recipe is in taking the risk and not knowing the outcome with any real certainty. Sometimes you turn a creative corner during a work and it takes on a whole new life because of one new idea or realisation and that slingshots you off in a new direction that can have consequences for the whole series of work.

You mention the architect “as fleeting shadow representing the transitory nature of their own involvement”. Could you elaborate on this?

The dance aspect of design can be complicated and becomes riskier the greater the level of complexity. Architects often face an ascending spiral of expectation. Each performance must be backed up with the next as good as and, preferably, better than the one that went before. In some ways the figures and buildings in Tattooed City represent that degree of difficulty, of striving, failure and success.

What informs your view of the “human form coiled, compressed or extended to achieve the required task”?

The sheer athleticism of the dancers/gymnasts provides a useful metaphor of architecture at its best – a grappling and clinging to ideas in the face of adversity. My images try to represent that dance and artistry. The reason memorable buildings are in short supply is that architects are either overlooked, or they fail; they fall and are swept aside. Even though some of the images from Tattooed City appear bleak or dark, there is also an uplifting and hopeful human spirit that aligns with those magical qualities of amazement and wonder about the best work.

Tattooed City was shown in Ballarat (as part of the Ballarat International Foto Biennale, August 19 – September 17, 2017). How was the exhibition received by the curators, organiser and visitors?

Ballarat just happened to be the host city. I don’t really see much of a correlation between my work and Ballarat. The human-like quality of skin and bones, for example, is playing with the idea that a building can have a certain life-force and meaning because of what has been invested in it. Buildings do acquire history and meaning and are stage-sets for all kinds of events, great and insignificant. Some more so than others. I’m much less interested in the postmodern association of buildings overt in their expression. The lace-like patterns and shadows of Victorian-era terraces, for instance, remind me of the effect achieved when a woman’s face was delicately patterned with a fascinator or veil. Photography can be the full mega-pixel blast, or veiled and abstracted. Images and architecture that are gentle can also be powerful and moving. They comprehend light – and shadow where something is left implied. This invites the viewer to do some of the work.

To put this in context, can you talk about your history as a photographer, publisher, writer, corporate communicator and anything else relevant from your varied career?

Steel Profile launched in March of 1981 when I worked in the corporate communications area of BHP. The steel division was a supporter and sponsor of architecture but not as an active participant. Steel Profile gave the initiative back to how a company could wisely, and creatively, invest its funds rather than simply handing over sponsorship money and hope for the best.

In many ways Vision is an evolution of Steel Profile but stands very much with its own identity. I began Vision for Pilkington the glass manufacturer (now Viridian) in 2002 a couple of years after my editorial position at Steel Profile ended (although I have remained a constant contributor as both a writer and photographer). Vision has changed from a printed to an e-magazine and in the past couple of years we have added video content. It comes out eight to nine times a year, and each issue runs to around 50 pages with two film segments where we interview the architects and put the moving image to work to reveal the design.

In both instances, my clients trust me to deliver a concept that would resonate with the readers/viewers. That’s a useful distinction now – we have viewers in addition to readers.

I have promoted the idea of good corporate citizenship by underwriting the recognition of outstanding design. It’s about rewarding people across creative and technical fields who use steel or glass in exceptional ways. In each case we have thrown away the whip of product promotion and told and photographed stories about ideas, beliefs and endeavour. And rather than only feature the usual design faces, we have tried to recognise emerging talent wherever possible.

My first book as writer and photographer, Local Heroes: Architects of Australia’s Sunshine Coast, was the result of covering the work of Gabriele Poole, John Mainwaring and Kerry and Lindsay Clare for over two decades for Steel Profile. I loved work so specific to place and time and yet timeless. And with such an authentic response to climate and place. Their design is full of humility yet audacious in its invention and simplicity.

Each publication and the video content are fuelled by ideas – the architects who my partner Jenny and I interview – and my own editorial view. Having a certain belief and confidence to present an editorial position is important and a valuable quality for these clients to ensure they are considered serious participants in the dialogue with their audience/readership.

I have been a keen photographer since my teens and so when the opportunity arose to use the camera professionally it felt entirely natural to utilise my curious eye. I studied professional and creative writing, majoring in scriptwriting at Victoria State College following early training as a journalist. All my writing experiences from poetry to technical writing inform how I see – and record – the world through the lens and on the page.

Why and when did you consider architecture and how did Steel Profile evolve?

Architecture, for me, was a bi-product of becoming more aware of a changing city in the 1970s. Wreckers and builders were demolishing the old world and creating the new. I simply made it my business to be curious about architecture. So, by the time I left journalism on suburban newspapers and writing, photography and film publicity roles, I was ready to bring those experiences into a single idea with the launch of Steel Profile. Working for BHP and the steel division specifically, I wanted to project the idea of molten steel translating into some extraordinary applications and my first story in the first issue of the magazine was with a then relatively unknown Glenn Murcutt. In many ways he was a sign of much greater things to come in Australian architecture and featuring him as the Cat on the Hot Tin Roof signalled an enduring regard and bond long before he received global plaudits.

It went from there. I accompanied him to Arnhem Land, New Guinea and Helsinki where we filmed his Alvar Aalto award in 1992 for the documentary I directed, titled Touch the Earth Lightly. I filmed him in Rome in 2002 accepting the Pritzker Prize. Interviewing and photographing some of the profession’s best has been highly motivating. (DS: Hyatt also profiled Murcutt for the 30th anniversary issue, in a tasteful homage to his influence.)

Inventing (for want of a better word) Steel Profile was very satisfying because I had to argue for the magazine to rise well above the perception by marketing people that it should become a product brochure. At the time of our launch there were relatively few design magazines – Belle, Vogue Living, Architecture Australia. It was interesting that Steel Profile became a collectable. Even after all these years, I’m asked for back copies or people tell me that they have collected every issue. (DS: The State Library of New South Wales has bound copies of 1980s and 1990s issues and then loose ones.) Commercial buildings, university campuses, aquatic centres, exhibition halls, museums, early days of sustainable projects, architects you instantly recognise and others less well-known; Steel Profile’s influence remains wide. It’s satisfying that corporations can demonstrate a more altruistic attitude when connecting with their stakeholder audience.

BHP’s support for Steel Profile included sending me to China, Japan and North America to discover a range of startling and innovative projects, all important to share with readers. Among them were Kengo Kuma’s sublime Atami Villa, Norman Foster’s exquisite HK Bank, Ed Niles’ climactic Sidley Residence, Malibu and David Ming Li-Lowe’s ground-breaking Earthquake House in Los Angeles.

There are inevitably commercial pressures to improve publications with product placement. Steel Profile identified and showcased interesting people and projects and did so without overloaded product placement or the dry reviews of the mainstream architecture press. By the mid-1980s we were also producing video content under the Steel Profile banner and this really gave the magazine a whole other voice.

One of the toughest aspects of the job is to develop an expertise as both writer and photographer while simultaneously shooting film for various documentaries on design. I still have to explain the various strands to some people who have trouble understanding the multiple roles my partner Jenny and I perform. Those creative and technical acts though never exist in isolation. Each creative act informs the other.

After taking city pictures over the years for residential and commercial projects, why, and when, did you decide to take more abstract, artistic portrayals of the city as in Tattooed City?

I’ve photographed architecture for more than 30 years. I’ve loved the challenge of capturing the defining image wherever possible. Photography is a form of distillation reducing form and space to its most elemental. Visual simplicity and elegance are key goals for me to help communicate the architect’s work in the most effective and artistic way possible. While much of my commercial work has indeed been commercial, I’ve always tried to bring a subjective eye to interpret rather than merely record.

My CV (see Bio below) is very different from most photographer’s working in the field. In the past few years I’ve tried to rely less on incoming calls for my work than to generate my own. I had a strong urge to consolidate all my experience and produce my own art rather than always responding to a brief. I’ve also just completed a manuscript for a novel with this very same title – Tattooed City.

What are your views on the role of the architect and architecture in shaping cities?

I’d much prefer architects be given greater scope and oxygen to contribute to our cities. Too often other forces – usually in the guise of committees or ‘collaboration’ – render architects impotent and unable to realise their vision. A tiny fraction of most cities reflect architecture and instead are the antithesis of great design. Unfortunately, cities are underwritten by wealth fund managers and large building groups who too rarely allow architecture to blossom. Great ideas are easily diluted by ‘value management’. Think of the great buildings such as the Sydney Opera House, Guggenheim in New York and Bilbao, Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank and a handful of jewel-like towers and dwellings. The architects are the deserved stars here because they had sublime vision and incredible resolve.

Do you think there is any hope that architects will be allowed to rise above forces such as committees and other bureaucratic collaboration, to produce great design and have that built, and have the mental strength to retain their “sublime vision and incredible resolve”. How important have you found the architect/client relationship to be in producing a great, memorable building?

It’s a fine line between collaboration and committee. Real collaboration is uplifting and inspiring while committees tend to tick all the boxes, which explains why we see so many big, boring building boxes. I can’t imagine a Sydney Opera House delivered by a committee, but it could occur through collaboration and singular vision.

Great ideas are very easily diluted by “value management” – it would be great if you could expand on this.

One of the major complaints I hear from architects on larger commercial projects especially, is the role of value management in diminishing and diluting real design vision. Great buildings require this vision along with an appreciation of the countless nuances that comprise the considerate, thoughtful building that inspires. Value management can easily discount and strip away the generosity of ideas and elements that ensure architecture is in perfect pitch with its place – much like an old-fashioned tuning-fork that identifies the right musical note. It’s easy to say: “Oh, you can do without those finishes, or that space”. Knocking ideas over is much easier than creating them.

In our documentary Heart of Glass on the making of 1 Bligh St. Sydney, you can rightfully say the architects Christoph Ingenhoven and Achitectus were the designers, but Victor Hoog Antink, the CEO of Dexus, championed that building at Board level to protect the generosity of ideas it contained. The architects acknowledge that. That role of patron saint, of informed benevolence, is essential in architecture and for that matter in photography and film-making.

The loss of those enriching components and parts convert greatness to mediocrity. Maximum net lettable floor area might immediately appeal to investors, but the lost delight of say, a mezzanine, forecourt landscape, rooftop garden, or use of inferior materials can be the difference between commercial success and failure over the longer term and come back to trash the investment.

Do you see your brand as the mix of writer, photographer and film producer?

I’m not sure how much early study was an influence. For me it’s what Ansell Adams referred to as: “You don’t make a photograph just with a camera. You bring to the act of photography all the pictures you have seen, the books you have read, the music you have heard, the people you have loved.” I’ve had various mentors along the way and mostly they have taught me to back my judgement rather than to continually look over my shoulder.

What is your novel about and in writing this are you responding to the DIY zeitgeist?

The novel is completed but is being polished. It’s about an architect who finds himself in a desperate plight financially and personally and wondering whether he’s up to a major design project that will either make or completely break him. Curiously I have run with the title Tattooed City. It has been written concurrently with my photographic work. In it the protagonist Samuel Buck has to face his own demons and those that surface as a result of his ambitions to leave a more altruistic, artful footprint rather than a pragmatic mediocrity.

In this age of the starchitect, how can this be reconciled with your view that “architecture is too easily steered off course by pragmatism – the precarious nature of design’s role as athletic yet vulnerable”?

In many ways the art of architecture has become the business of architecture and while that’s necessary, something has been lost in the process. Predominantly business-driven, architects sometimes lose sight of the loveliness that can flow from creating work that is challenging, magical or beautiful. Risk-taking can be of the informed type rather than the crazy variety. That’s a big part of the creative process.

And next?

I’m in the early stages of producing a documentary that brings together the lives of the authors Suzanne Chick, her mother Charmian Clift and George Johnston. Chick’s discovery of her birth mother and subsequent publication of Searching for Charmian in the 1990s has remained with me. This film project will realise my long-held interest in the lives and literature of this trio.

Bio: Melbourne-based writer, photographer and filmmaker; specialises in architecture; written and photographed eight non-fiction books including Local Heroes – Architecture of Australia’s Sunshine Coast (Craftsman House Press), The Games Show – Australia 2000 (self-published), Out of Town (Images Publishing), Great Glass Buildings – 50 Modern Classics (Images Publishing), Masters of Light (Images Publishing) and Art House – Queensland Gallery of Modern Art (Thames and Hudson).

Founding editor of Steel Profile (1981-2001) and Vision (2002-2018); documentaries include Sir Norman Foster, Sir Richard Rogers, Glenn Murcutt – Touch the Earth Lightly, Heart of Glass – 1 Bligh St. Sydney, and Transformer – Chifley Tower by Rogers, Stirk and Lippman Partnership.

Produced some 50 film shorts on architecture and design under the Vision banner; with his wife and business partner/photographer Jennifer, established an online fine-art photographic gallery and film resource; finalist in the 2016 Bowness Photographic Prize; Tattooed City series featured at the Ballarat International Photo Biennale; https://hyattgallery.com.au/